Case Study Research Report:

Learning Management System utilisation by teachers and students at a regional Victorian school.

How well are the affordances of the SIMON LMS being used by teachers and students in one specified school setting?

Executive summary:

Learning Managements Systems (LMS) are web based products which have been used by most universities for a significant period of time. Increasingly schools, particularly at the secondary level, are also investing in such digital tools. This study compares the potential usage of a specific LMS in a small, regional, kindergarten to Year 12, Victorian Independent School with those aspects that teachers and students are actually using. Information was garnered by use of online surveys, and the findings suggest not only wide acceptance of some affordances by both teachers and students, but also ignorance of the potential of others. The Primary Campus usage is minimal, for a number of reasons. The data were comparable with results obtained by researchers working on LMS reviews in other institutions, predominantly universities.

The Nature and Context of the Case Study:

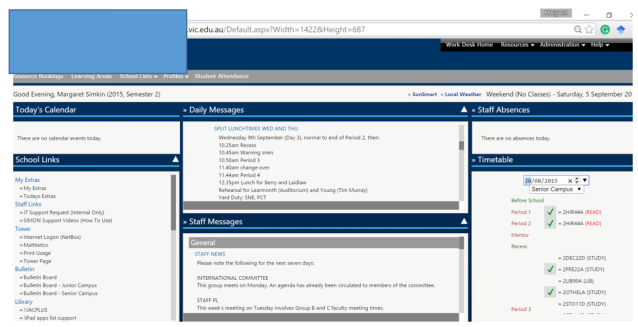

This case study report presents the results of an empirical inquiry investigating the extent to which the SIMON (LMS) (SIMON Solutions, 2009), as one example of a contemporary educational phenomenon, is being used to improve teaching and learning within the context of a specific regional Victorian school. The inquiry was framed to discover the degree of usage by teachers and students, the individual uptake of those functions offered by the LMS compared to features not adopted, and the perceived advantages, problems and potential of this specific educational software. The underlying purpose was to understand user needs and perspectives, thereby identifying aspects of usage with which users of this LMS may require support, in order to improve the school’s knowledge networking and opportunities for digital innovation.

Terminology:

LMS, also referred to as Virtual Learning Environments, Digital Learning Environments, Course Management Systems or Electronic Learning Environments are web based applications which are accessible wherever an Internet connection allows (De Smet, Bourgonjon, De Wever, Schellens, & Valke, 2012, p. 688). While a significant amount of research has been conducted on the impact of such systems in universities, where, for example, uptake in Britain by 2005 was reported at ninety five percent (McGill & Klobas, 2009, p. 496), there are fewer examples focused on schools, and these are not K-12 settings. The circumstances of the chosen setting are therefore different to those institutions reported on in other academic literature.

SIMON is a learning management program, created in 2000 by practicing teachers at St Patrick’s College in Ballarat (Simkin, SIMON, 2015 c). It is now owned by the Ballarat Diocese and the original developers are still involved in managing its evolution. Whilst originally used in Catholic schools within this Diocese, SIMON usage has extended to other educational jurisdictions and Australian states. The school on which this case study focuses, was one of the first Independent Schools to adopt the program, moving to SIMON from Moodle about five years ago. It has also developed a relatively collaborative relationship with the founders of the LMS, by suggesting possible changes; an aspect of the specific context that does not apply to many other schools using the same product.

Constraints:

The decision to focus on reviewing one LMS in a single school, was selected to meet the constraints of the timeframe available for conducting the research, and the stipulations outlined for the writing of the research report. The chosen school has been using SIMON for six years, however employment of the system has been observably inconsistent from both a teaching and learning perspective. There is, therefore, potential to use the findings of this investigation to lead to improvement. Three forms of understanding are required before educational transformation can occur: a critique of the current, a vision of the desired and a theory for guiding the situation from where it is to where it should be in order to achieve better outcomes (Robinson & Aronica, 2015, p. 58). This sentiment encapsulates the intention of this case study research as investing in an LMS should result in measurable return on investment (Leaman, 2015, para 1).

The Process:

Literature Review:

The process necessitated commencing with a review of relevant literature, taking guidance from Thomas, the quality of material and the publications it was coming from were the first criteria, including following up references to literature reviewed within the sources investigated (Thomas, 2013, pp. 60-61). Most titles were retrieved from the university library, but one was provided through a Twitter connection which led to Professor Harland (Maleko, Nandi, Hamilton, D’Souza, & Harland, 2013) and another from a colleague, an intriguing and very specific research proposal highlighting issues which apply to segregated education, but which also reminded of the challenges of mixing methodology, and that awareness is not the same thing as use when it comes to LMS (Algahtani, 2014, p. 16). These papers revealed some common themes surrounding LMS research, as outlined below.

Commonalities:

Research has predominantly considered the major LMS providers, notably Blackboard (which now incorporates WebCT and ANGEL (Islam, 2014, p. 252)), but also Dokeos, Smartschool (De Smet, Bourgonjon, De Wever, Schellens, & Valke, 2012, p. 689), Sakai (Lonn & Teasley, 2009, p. 687), Desire2Learn (Rubin, Fernandes, Avgerinou, & Moore, 2010, p. 82) and the popular open source Moodle. Some papers analyse usage of several LMSs, while others compare the utility offered by different options such as Facebook (Maleko, Nandi, Hamilton, D’Souza, & Harland, 2013, p. 83), and SLOODLE (Moodle incorporated with Second Life as a 3D virtual learning environment) (Yasar & Adiguzel, 2010, pp. 5683 – 5685).

The majority of the literature was based on surveys, so the decision to collect information through online surveys was validated. Given that the SIMON interface is different for teachers compared to students, two surveys were required. These were constructed using Google Forms.

Limitations:

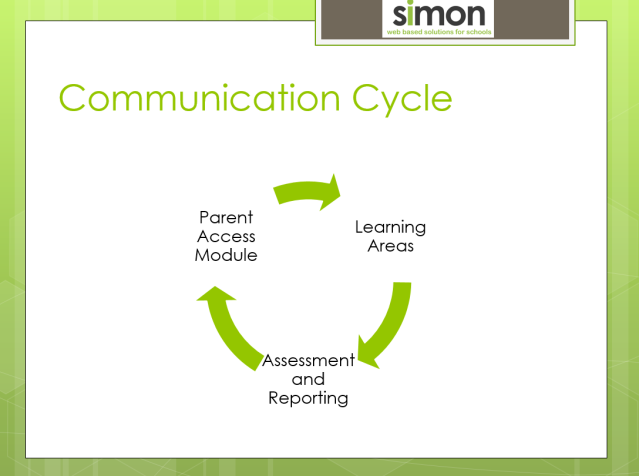

A Parent Access Model survey is being developed for future use to strengthen the evaluation process and enhance the practical application of the recommendations. Lack of time and access to this module for the researcher precluded it from the case study. Use of SIMON by the Primary Campus would benefit from further discussion also. Analysing the purpose and style of the questionnaire was a vital stating point (Elias, 2015), therefore the main elements of Elias’ work informed the overall structure (Simkin, 2015 a).

Survey Methodology:

Qualitative and quantitative surveys elicit very different information, and the literature review resulted in the decision to incorporate both styles of questioning. Qualitative methodology enables detailed descriptions to be provided that are not constrained by the researcher, enabling the respondents to elaborate on the things that matter to them (Ritchie, 2013, p. 4). The style of qualitative questions accessed aspects of critical theory enabling an understanding of the intersect between material conditions and their influence on human behaviour (Ritchie, 2013, p. 12). For example, the last two questions on both surveys (Appendix pages 23-25; 34-35) were ontologically focussed, aiming to compare realistic responses with idealistic possibilities.

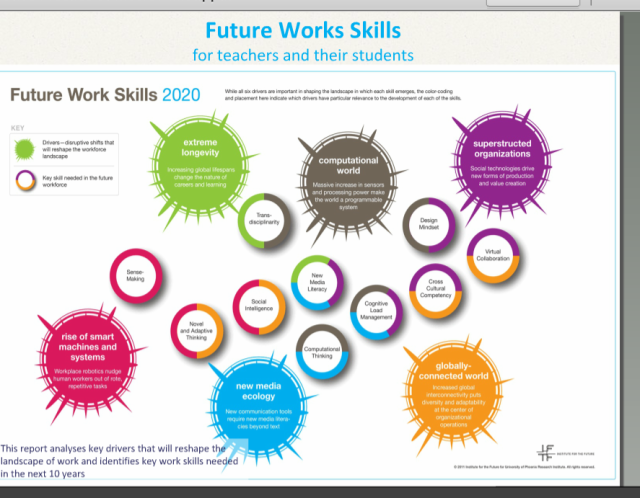

Selecting the right tool for the anticipated outcome also required quantitative data gathering: deciding appropriate topics to assess by checklists (Appendix pages 20 & ) compared to items that needed to be evaluated through Likert scale questions (Appendix page) followed (Thomas, 2013, pp. 209-215). It was important to set such questions up in a neutral manner, rather than in a way that directed the result to meet preconceived ideas; commencing with the Likert style questions using a scale of one to five (with one the lowest and five the highest level of agreement) allowed participants to proceed quickly through the quantifiable elements while offering a nuanced range of responses (Thomas, 2013, p. 214). This style of “scale” question allows for opinions to be presented easily; for those who like to explain in more detail, and to have open ended and creative thoughts, the qualitative examples were provided later in the survey (Thomas, 2013, p. 215). Questions needed to cover contextual, explanatory, evaluative and generative options (Ritchie, 2013, p. 27) to allow this report to describe and critique the current, suggest what might be possible and enable recommendations that might be educationally transformational (Robinson & Aronica, 2015, p. 58). The final questions were designed to evoke creative responses and raise the potential for the future of LMS for the next generation of learners, where the ideal system should be more of a learning environment or ecosystem, fitted together in the manner of building blocks to suit subject specific requirements (Straumsheim, 2015, p. 7).

In order to ensure clarity and precision (Thomas, 2013, p. 207), the surveys were trialled with fellow university students and work colleagues, including the school’s technical staff, who have strong knowledge of SIMON. Despite this there were some elements that might have offered a different insight: gender and year level of students for example and teaching methods of the staff; such omissions are typical of mixed method research, and hard to avoid in short time frames, especially by relatively inexperienced researchers as myself (Algahtani, 2014, p. 16).

The anticipated findings were targeted at establishing the overall satisfaction and learner engagement with SIMON’s functions in terms of organisation, pacing of work, access to resources, collection of materials, class discussion, and feedback, as outlined in the work of Rubin et al (Rubin, Fernandes, Avgerinou, & Moore, 2010, p. 82). The study had to identify the enabling functions as distinct from the hindrances, and whether they were impacting on design of and access to course materials in a positive or negative manner (Rubin, Fernandes, Avgerinou, & Moore, 2010, p. 82). Ease of navigation and number of clicks to access items can facilitate learning, where the inverse will frustrate users and lead to avoidance of features; this is particularly true of feedback. If Blackboard v.12 took twelve click to achieve something that Moodle could do with one, how did SIMON compare (Rubin, Fernandes, Avgerinou, & Moore, 2010, pp. 82-83)?

Critical Evaluation:

The Survey Findings:

The survey resulted in thirty-three teacher and sixty-eight student responses, or 47% and 31% respectively. All teaching staff were invited to participate, but only one Junior Campus teacher accepted the opportunity. Another emailed and said it wasn’t really relevant to them. Given that these teachers generally only use a small number of SIMON’s features this was not unreasonable. Teachers on small part-time loads were also not expected to participate; therefore this result was better than expected in the last week of term. Students from Year Nine to Year 12, who have one to one device access were the target population, and the number of respondents for the busy last week was also pleasing.

While every recommended avenue had been explored in terms of how to set up a valid survey instrument and pretesting had occurred (Elias, 2015), there were still unexpected outcomes. Omissions and problems arose from the survey’s construction. It would have been helpful to know the gender of recipients given that this has been a factor in a number of other research results, not only Algahtani’s where such issues would be expected (Algahtani, 2014). It would also have been helpful to ascertain the teaching areas of the staff, relative age group of each teacher (or years of experience), and the year levels of the students as was done by Kopcha (Kopcha, 2012, p. 1116). Including questions to elicit this information would have enabled more targeted recommendations.

The use of Likert scale questions in the introductory part of the survey worked well, and respondents benefitted from having a five point scale. The usage responses indicated that 28% of teachers (see teacher and student results below) believe that they use SIMON to some extent or a great extent, while 53% of students (see teacher and student results below) reported that their teachers used SIMON at this level. This is an example where interpretation of results would have been more meaningful if the subjects being taught were known. Staff and students were generally more positive that SIMON supported their teaching and learning in some manner than they were negative.

Another anomaly of the type referred to above was revealed by the yes or no option relating to the uploading of work question (see teacher and student results below) where 81% of teachers reported that they did not ask students to do this, but 31% of students said that they did provide work to their teachers in this manner. An astonishing percentage of students reported video and audio feedback being provided (71%) where only 24% of teachers said that they provided this (see teacher and student results below). A follow-up question here on which subjects were making use of this facility would have been beneficial in terms of recommendations, especially if responding teachers had been asked to indicate their faculty.

Moving from Likert scale questions and yes or no option to open-ended responses proved valuable on both surveys, as had been anticipated. The number of respondents who completed these optional questions was very pleasing. The slight difference in questions between the two surveys was deliberate to allow for the differing access teachers have to the LMS compared to students. The responses to most of the common questions demonstrated a close correlation between teacher understanding and student use, with a couple of exceptions such as those outlined above.

A summation of feelings towards the LMS elicited by the surveys indicated a strong acceptance of the technology. This has been written about by researchers reviewing usage through technology acceptance models (TAM) (De Smet, Bourgonjon, De Wever, Schellens, & Valke, 2012, p. 689). As the school community concerned is technologically experienced, this was expected. Results also demonstrated that while many users verbally describe a love-hate relationship with SIMON, the use of survey methodology produced more considered feedback (Straumsheim, 2015, para 3). Of the eighteen affordances Schoonenboom lists as desirable in an LMS fourteen are possible using SIMON; only meetings, online examinations, peer feedback, and open hours are not possible in the same manner as she describes (Schoonenboom, 2014, p. 248). Interestingly, the questions aimed at improving SIMON (17 – 19 for teachers and 18 – 19 for students) did not request any of these aspects be made available.

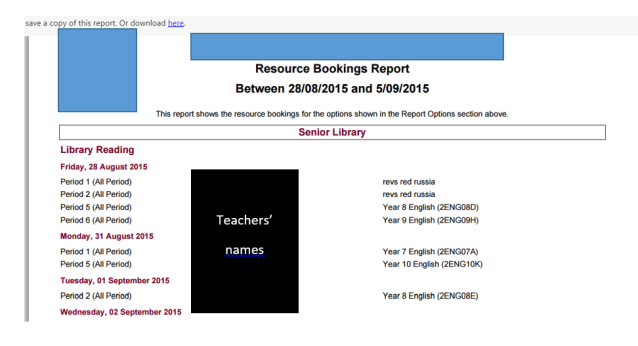

The broad overview of the findings from the open-ended comments (Appendix page) indicated that teachers enjoy the reporting facility because it links to the assessment module and saves them work. The most frustrating facet for both teachers and students is the number of clicks it requires to access work (51%). Students highlighted the inconsistent usage of the LMS by their teachers, and sometimes indicated that components are being incorrectly used: all student work should be in the “curriculum documents” section but some teachers are placing it in “general documents”. While there is an historic reason that may have led to this, it should no longer occur. Reporting live through assessment tasks should indicate more clearly that work is linked to the curriculum module.

Facets identified:

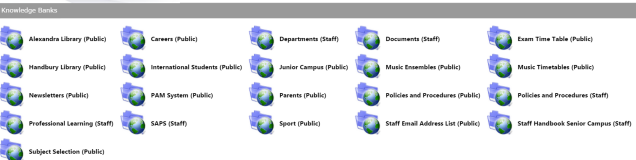

Five equal facets should be provided by any LMS: interoperability, personalisation, analytics, collaboration and accessibility (Straumsheim, 2015, para 6), and, according to the findings, SIMON delivers all of these to some degree. Taking interoperability first, it most elearning tools that teachers currently use with their classes can be accommodated, either by linking the document to the system (such as collaborative OneNote notebooks), locating a file in the system, or providing a weblink.

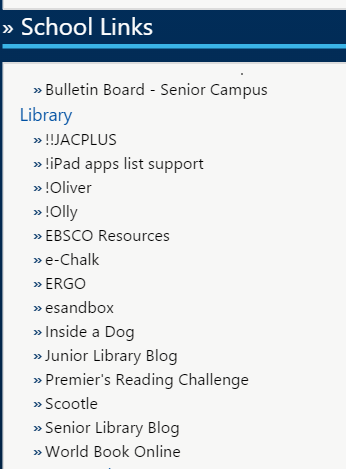

Personalisation is also possible and has led to some confusion as evidenced in the responses. The school concerned has added a number of links, for example, to library services, which some respondents find bewildering. It does however correspond to the findings reported by Horn et al that a range of “library help objects” and links to resources accounts for user differences and support needs (Horn, Maddox, Hagel, Currie, & Owen, 2013, pp. 238-240).

Analytics are available to teachers for administrative use, such as knowing if a student is present or has submitted their work, and also to the LMS administrator for checking the number of log ins for example. The teacher who suggested that it would be good if SIMON could calculate School Assessment Percentages (currently done through Excel 365) would be surprised to know that with teacher education in derived scores, it could.

Collaboration was not raised by respondents, although some referred to using the forum space. This is probably SIMON’s weakest suite, but looking at what is planned for the next software update, school, parent, student interaction should be improved (Simkin, 2015 c). Lonn and Teasleys’ research indicates that few users used or rated the interactive tools, preferring to comment on the tools that push out to or collect work from students (Lonn & Teasley, 2009, p. 693). Collaboration through internal communities of practice and self-organising networks should become more common in the near future as more teachers look to make global connections, and the Senior Campus moves to a one-to-one device model in 2006 (Archer, 2006, p. 67)

In terms of accessibility, one teacher, who followed up on his survey by sending an email with more detailed information (Budenberg, 2015), found that most of his issues were due to lack of instruction during orientation. In a meeting to resolve some of his issues, Tim passed a comment that SIMON was like a Swiss army multi-purpose knife, citing almost word for word a comment from Alier et al which alludes to the fact that numerous tools, while helpful, may not offer the best solution for the purpose (Alier, et al., 2012, p. 107). His prior experience with Daymap, an LMS with the ability to email parents of a class with one click, was raised face-to-face. SIMON is a much cheaper solution.

Recommendations:

The case study has achieved its goal of leading to a number of recommendations for the school under evaluation. Given that no LMS will answer everyone’s needs, it is better to work with the one that is currently provided and maximise its strengths while minimising its weaknesses (Leaman, 2015 para 7). In this setting there is the added benefit of access to the developers.

The following recommendations will be passed to the designated, relevant groups.

For SIMON developers:

- While interoperability between a range of platforms and SIMON is good, retrieval of information in terms of convolution (number of clicks) and lack of search functionality is a hindrance. This requires simplification in some form.

- Collaboration through a range of means: chat, peer assessment and an improved forum interface would be well regarded as beneficial to communities of practice.

For the School Executive:

- More effective mentoring of new teachers and ongoing in-servicing of all teaching staff would improve usage for students, thereby enhancing learning.

- A clear and consistent statement of expectations for usage by teachers appears to be unclear. Teachers need to model SIMON usage to students more effectively.

For the Teaching and Learning Committee:

Discussion is required to consider the following:

- Options for the provision of face-to-face assistance with SIMON mastery need to be provided for teachers and students (beyond their faculty or subject teachers).

- Opportunities for learning new aspects of SIMON at relevant times, for example when software is upgraded.

- Which LMS facets that may be suggested in other systems are missing from SIMON that are considered desirable.

- These survey findings – to enable improved practice.

For the Information Services Department:

- That the location of library related information within the LMS be revisited and evaluated in terms of the most effective location/s for accessing them.

Conclusion:

The school studied has been using the SIMON Learning Management System for several years yet the uptake varies enormously. Some teachers and students rarely use it, others use all aspects of it really well. The reporting package is compulsory and has been effectively used and appreciated by most teachers. Usage of the other features has been inconsistent. This report reveals those elements that have been used, the users’ experience with the LMS, and the outcomes that have been enabled for them through such use. It is important to determine why some elements have been used, and others avoided. Steps should be taken to improve use, and consider the potential impact of change for learning.

References

Algahtani, M. (2014). Factors influencing the adoption of learning management systems in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabian Universities by female academic staff. Research proposal for confirmation of candidature (PhD) DR209 16th July 2014. Received by personal communication from Bradbeer, Susan, through a dropbox link provided by a lecturer at RMIT, 17 September 2015

Alier, M., Mayol, E., Casan, M. J., Piguillem, J., Merriman, J. W., Conde, M. A., . . . Severance, C. (2012). Clustering projects for interoperability. Journal of Universal Computer Science, 18(1), 106-222.

Archer, N. (2006). A Classification of Communities of Practice. In Encyclopedia of Communities of Practice in Information and Knowledge Management (pp. 21-29). Informationn Science Reference (an imprint of IGI Global).

Budenberg, T. (2015, September 16). personal email. A request for your assistance.

De Smet, C., Bourgonjon, J., De Wever, B., Schellens, T., & Valke, M. (2012). Researching instructional use and the acceptation of learning management systems by secondary school teachers. Computers & Education, 688-696. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.09.013

Elias, L. (2015, February). Intelligent Questionnaire Design for Effective Participant Evaluations. Training and Development, 8-10.

Horn, A., Maddox, A., Hagel, P., Currie, M., & Owen, S. (2013). Enbedded library services: Beyond chance encounters for students from low SES backgrounds. Australian Academic and Research Libraries, 44 (4), pp. 235 – 250. doi:10.1080/00048623.2013.862149

Islam, A. N. (2014). Sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with a learning management system in post-adoption stage: a critical incident technique approach. 249-261. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.09.010

Kopcha, T. J. (2012). Teachers’ perceptions of the barriers to technology integration and practices with technology under situated professional development. Computers & Education, 1109 – 1121. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.05.014

Leaman, C. (2015, August 20). What If Your Learning Management System Isn’t Enough? Retrieved from eLearning Industry: http://elearningindustry.com/learning-management-system-isnt-enough

Lonn, S., & Teasley, S. D. (2009). Saving time or innovating practice: Investigating perceptions and uses of Learning Management Systems. Computers & Education(53), 686–694. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.04.008

Maleko, M., Nandi, D., Hamilton, M., D’Souza, D., & Harland, J. (2013). Facebook versus Blackboard for supporting the learning of programming in a fully online course: the changing face of computer education. Learning and Teaching in Computing and Engineering, pp. 83-89. doi:10.1109/LaTiCE.2013.31

McGill, T. J., & Klobas, J. E. (2009). A task-technology fit view of learning management system impact. Computers & Education, 496 – 508. doi:10.1016/j.compendu.2008.10.002

Ritchie, J. L. (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Great Britain: Sage.

Robinson, K., & Aronica, L. (2015). Creative Schools: Revolutionizing Education From The Ground Up. Melbourne: Allen Lane.

Rubin, B., Fernandes, R., Avgerinou, M. D., & Moore, J. (2010). The effect of learning management systems on student and faulty outcomes. Internet and Higher Education, 82 – 83. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.008

Schoonenboom, J. (2014). Using an adapted, task-level technology acceptance model to explain why intsructors in higher education intend to use some learning management system tools more than others. Computers & Education, pp. 247 – 256. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2013.09.016

Simkin, M. (2015 a, August 17). Article review. Retrieved from Digitalli: http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/msimkin/2015/08/17/article-review/

Simkin, M. (2015 b, October 6). SIMON. Retrieved from Digitalli: http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/msimkin/2015/10/06/simon/

SIMON Solutions. (2009). Retrieved from SIMON: http://www.simonschools.net/about-simon.html

Straumsheim, C. (2015, May 11). Brick by Brick. Retrieved from Inside Higher Ed: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/05/11/educause-releases-blueprint-next-generation-learning-management-systems

Thomas, G. (2013). How To Do Your Research Project; A Guide For Students in Education and Applied Social Science. London: SAGE.

Yasar, O., & Adiguzel, T. (2010). A working successor of learning management systems: SLOODLE. Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences 2, 5682 – 5685. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.928