Exegesis:

Below is the text for Assignment 1, which accompanies the Digital Artefact.

This exegesis evaluates the digital artefact: “Social media in your classroom”, a short animation, constructed using Sparkol VideoScribe software (http://www.sparkol.com/) (Simkin, 2015). This platform was chosen because it contains copyright free sketches and music, offers effective conversion of text and photograph to hand drawn images, and renders into upload-ready film. Scribing animation has been proven to attract and hold viewers’ attention, an important requirement for the artefact. (Air, Oakland, & Walters, 2014). Content was developed using appropriate design principles, based on ADDIE (ADDIE Model, n.d.), selected for simplicity, and application to andragogy. A broad application of knowledge networking theory: physical connectivity, and developing collaborative communities of practice, democratising learning, was the intended message (Price, 2015).

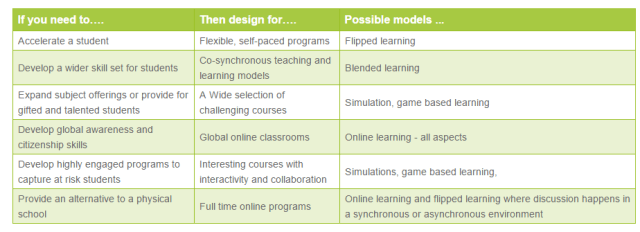

Design commenced with ADDIE’s analysis phase; this clarified instructional objectives, identified the learning environment and acknowledged the audience’s pre-existing knowledge and skills. Informed by the school’s technological vision, the artefact needed to stimulate technology inclusive pedagogy, for 2016. Its purpose needed to be effective, accessible and developed at minimal cost. Modelling a product that could be re-used, or stimulate creation of new artefacts was important.

The form and function needed to engage teachers with the content of the artefact. The selection of VideoScribe over Powtoon, or Office Mix for PowerPoint was made because this style of video is persuasive, and well received (Air, Oakland, & Walters, 2014, p. 3). A comparison with these other products made it a clear winner (Simkin, Artefact Design, 2015).

One of the advantages of scribing is the stimulation of viewer anticipation (Air, Oakland, & Walters, 2014, p. 17). By using drawings to convey meaning, questioning is encouraged, and an element of playfulness produces a positive emotional response (Barrett, 2013, pp. 53-56).

Content was structured to avoid the pathology of Information overload (Bawden & Robinson, 2009, p. 182). Being mindful that teachers’ primary focus is facilitation of the learning was critical for selecting the drawings and words included in the animation. The message that the connected world lies at the heart of the curriculum was crucial (Zuckerman, 2013, p. 266).

Technological challenges affected design. Overall length was reduced to enhance rendering to film and reduce upload speeds. Some desired elements had to be removed, and the spoken narration abbreviated (Simkin, Artefact Design, 2015). Human resources were stretched in terms of pre-existing skills, time and looming deadlines, which impacted quality of the finished product. Such factors will always affect teachers creating digital artefacts for their learning communities.

The context for any digital artefact is the most critical consideration. The region for which this artefact is intended suffers patchy Internet access, so brevity and file size were critical. The clientele comprises a school community seeking to implement higher order technology skills though incorporation into lesson design. The teachers are academically focussed and technologically competent. For the last eleven years, they have used tablet laptops, s their students from Years 9 upwards since 2012. Next year this will extend from Years 6 to 8 with iPads. Recent meaningful change in technological pedagogy in some classes, has sparked momentum on which to build.

Professional learning has offered limited opportunities for meaningful exploration of twenty-first century fluencies, or consideration of the importance of global digital citizenship, the background of core values and personal identity on which all other fluencies depend (Crockett, Jukes, & Churches, 2011, pp. 79 – 82). Some believe that teaching such skills is not the responsibility of subject teachers, however, the Australian Curriculum defines such skills as cross–curricular capabilities (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, n.d.). A professional learning day focussing on technology in the classroom is planned for the beginning of Term 3.

Artefact design commenced amidst discussion centred on the type of devices, which cannot create student centred learning environments themselves. The value of technology, with its ability to access, store, manipulate and analyse information, comes from creating a student-centred learning environment, and it is this that must be explored (Wong, Hanafi, & Sabudin, 2010, p. 389). Implemented well, social media ensures that students will spend less time gathering information, and more time reflecting on the objectives they have set, and the learning they have achieved (Wong, Hanafi, & Sabudin, 2010, p. 389).

This artefact, therefore, is aimed at andragogy, which identifies different learning needs to pedagogy (Couros, 2010, p. 113). Motivation for developing new skills is enhanced by adults’ life experiences, so it is vital to consider these needs, and present content of relevance (Couros, 2010, p. 114).

The starting slide was chosen to cause a positive response; smiling before you start recording your voice-over makes you sound upbeat, seeing a smile engenders a degree of optimism (Air, Oakland, & Walters, 2014, p. 46). With scribing, there is also the anticipation of what will appear next: why is this person smiling at me? The evaluation team has reported that this design element is successful.

Adult learners also draw constructive conclusions from mistakes (Couros, 2010, p. 114). A slight slip up in recording the voice-over remains, partly for this reason, but also because of the impending deadline. In the professional learning workshop this will provide a teachable moment. The effectiveness of this cannot yet be evaluated.

Educators face constantly altering expectations, from authorities rewriting curriculum, to administrators changing expectations, and alterations to school policies that cover every aspect of their working life. Therefore it was important that the message imparted by the artefact introduced a new way of working that was easy to adopt, and which offered a way of fulfilling current programs as outlined by the school’s professional learning policy documents. The recently introduced foci on considerations for successful learning experiences within a positive education framework have been effectively woven through the artefact (Grift & Major, 2013).

The social media focus was chosen for its personal familiarity to many teachers; it offers a range of options and is something that can be supported by current “nodes” of networked educators within the college learning community. Richardson recommends that these impassioned teachers have the capacity to assist others to become part of knowledge networks, a powerful way to deal with the vast quantities of accessible information (Richardson, 2010, pp. 295-296). Trials have proven the artefact’s efficacy in arousing interest.

The development phase reflected the need to justify trying social media rather demonstrating how to use it. Such Instruction will follow the viewing of the artefact, and will be able to unfold as participants require. While blogging is the specific media covered within the artefact, it is presented as an option, thus allowing for the ensuing discussion to lead to other examples. The skills of sharing authentic publications, reflecting on progress, creating positive digital footprints and co-learning through collection, curation and evaluation of information are the skills that matter, and which have been clearly articulated throughout the artefact (Richardson, 2010, pp. 297-301).

Social media has the capacity to be applied to any content, as indicated in the artefact. The specific example of Gail Casey will be raised in the ensuing discussion. She promotes a social and participatory approach within her face-to-face Mathematics classes, and builds on her students’ life experiences (Casey, 2013, pp. 60-63). Her work supports the considerations for learning design raised by Grift and Major (Grift & Major, 2013), and the power and multimodality of social media strengthen interdisciplinary literacy (Casey, 2013, p. 60). Brevity constraints precluded the inclusion of such justification for using social media.

Contrary to popular perception, students struggle with interpreting, thinking with, or building multimedia communications and need guidance to develop a multimodal literacy. (Lemke, 2010, pp. 250-251). Many myths abound in relation to older and younger users of technology; while younger people use social media in many forms, they do not realise the potential for learning and knowledge building that it offers (Higgins, ZhiMin, & Katsipataki, 2012, p. 20). Some wonderful images supporting this point had to be removed to allow successful rendering. The message that platforms are so varied and information access so big that no users can know them all could have been more effectively delivered (Weinberger, 2011).

Several invitees have been approached to review the artefact and give feedback as to its value; their comments support VideoScribe’s claim that scribing attracts and holds viewers’ attention (Air, Oakland, & Walters, 2014, p. 3). The artefact has been described as awesome, but assessing the delivery of the message has been difficult. The most evaluative comment identified the core message, and stated a need for more examples and information on how to get involved (Statt, 2015). This indicates that the intention of raising awareness and arousing interest in further involvement has been achieved for this viewer.

Rheingold identifies three aspects relevant to the power of knowledge networking through social media and thriving in an online environment. Firstly, attention, sometimes referred to as multi-tasking, or hyper-attention (attention splitting) (Rheingold, Netsmart: How To Thrive Online, 2012). This aspect of using digital devices is a concern for many teachers. Rheingold suggests that the solution lies in teachers’ design of learning experiences, which should include training as to when and how to apply the “high-beam light of focussed attention” (Rheingold, Netsmart: How To Thrive Online, 2012). In contrast, Andersson et al. report that students feel that laptops have substantially increased distractions and reduced face-to-face social interaction (Andersson, Hatakka, Gronlund, & Wiklund, 2014, pp. 43-44). The narration within the artefact successfully refers to the importance of social media for teaching students appropriate use and meaningful interaction as part of a range of strategies, thereby offering solutions for such concerns.

Secondly, becoming an active citizen in the online space, not a passive consumer, creates a literacy of participation (Rheingold, Attention, and Other 21st-Century Social Media Literacies, 2010). Collaboration moves combined efforts from merely co-operating to really working with others; collective learning in a shared domain of human endeavour is referred to as communities of practice (Wenger, 2012, p. 1). It is the potency of this mix of ages, experiences and knowledge seeking that is so attractive within social media options. The artefact presents this concept through images of face-to-face talking, and circles around the globe, supported by the narrative discussing the links to the world beyond the classroom, irrespective of time and location. The link between these processes, and their current use by universities and workplaces, clearly reinforces the importance of such skills (Christozov, 2013, pp. 1-3).

Finally, Rheingold nominates critical consumption, an issue raised by many others (Rheingold, Netsmart: How To Thrive Online, 2012). Knowing how to use social media to cultivate and utilise networks for learning must be modelled and encouraged by educators. This presents an exciting proposition, offering fulfilment of great hopes while simultaneously challenging many concepts of traditional schooling; the artefact presents this quite well. (Richardson & Mancabelli, Personal Learning Networks: Using the Power of Connections to Transform Education, 2011, pp. 7-8).

Blogging, the example focussed on within the artefact, has developed into a serious means of communication, which for many readers supersedes traditional news media (De Saulles, 2012, p. 15). It offers authentic publication, and a means of quickening the dynamic exchange of ideas, taking teachers from isolated classrooms to virtual spaces where generation of ideas propels innovative ways of becoming involved (Davidson & Goldberg, 2010, p. 176). The potential of connecting with a world-wide network of professionals for support and learning is successfully conveyed by this digital artefact according to viewer feedback (Wheeler, 2015).

Including research findings indicating a correlation between effective technology integration and improved learning outcomes has also resonated (Picardo, 2015). The artefact’s content inclusion, quality of product and download speed have been successful, however, the educational impact is unknown. The real value will only be observable after the workshop if it results in implementation of social media within this targeted school community.

References

ADDIE Model. (n.d.). Retrieved March 25, 2015, from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ADDIE_Model

Air, J., Oakland, E., & Walters, C. (2014). Video Scribing; How Whiteboard Animation Will Get You Heard. Sparkol Limited.

Andersson, A., Hatakka, M., Gronlund, A., & Wiklund, M. (2014). Reclaiming the Students – Coping With Social Media in 1:1 Schools. Learning, Media and Technology, 39(1), 37-52. doi:10.1080/17439884.2012.756518

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (n.d.). Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Capability. Retrieved from Australian Curriculum: F-10 Curriculum: http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/generalcapabilities/information-and-communication-technology-capability/introduction/ict-capability-across-the-curriculum

Barrett, T. (2013). Can Computers Keep Secrets? How A Six-Year-Olds Curiosity Could Change The World. Edinburgh: No Tosh.

Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2009). The Dark Side of Information Overload, Anxiety and Other Paraxes and Pathologies. Journal of Information Science, 35(2), 180-191.

Casey, G. (2013, September). Interdisciplinary Literacy Through Social Media In the Mathematics Classroom: an Action Research Study. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 57(1), 60-67.

Christozov, D. (2013). Knowledge Diffusion via Social Netwroks: The C21st Challenge. International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence, 4(2, April-June), 1-12.

Couros, A. (2010). Developing Personal Networks for Open and Social Learning. In Emerging Technologies in Distance Education (109–128). Athabasca University: AU Press. (pp. 109-128). Athabasca University: A U Press.

Crockett, L., Jukes, I., & Churches, A. (2011). Literacy is Not Enough, 21st-Century Fluencies for the Digital Age. Corwin.

Davidson, C. N., & Goldberg, D. T. (2010). The Future of Thinking: Learning Institutions in a Digital Age. Cambridge: MIT Press.

De Saulles, M. (2012). New Models of Information Production. Information 2.0: New Models of Information Production, Distribution and Consumption., 13-35.

Grift, G., & Major, C. (2013). Teachers As Architects Of Learning: Twelve Considerations For Constructing A Successful Learning Experience. Moorabbin: Hawker Brownlow Education.

Higgins, S., ZhiMin, X., & Katsipataki, M. (2012). The Impact of Digital Technologies on Learning. Durham University. Durham: Education Endowment Foundation. Retrieved from Education Endowment Foundation: http://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/uploads/pdf/The_Impact_of_Digital_Technologies_on_Learning_(2012).pdf

Lemke, C. (2010). Innovation Through Technology. In C21st Century Skills: Rethinking How Students Learn (pp. 243-274). Bloomington: Solution Tree.

Pearce, J., & Bass, G. (2008). Technology Toolkits: Introducing You to Web 2.0. South Melbourne: Cengage Learning.

Picardo, J. (2015, March 22). What Impact? 5 Ways to Put Research into Practice in the 1-to-1 Classroom. Retrieved March 23, 2015, from Educate 1 to 1: http://www.educate1to1.org/technology-impact-research-into-practice/

Price, D. (2015, March 23). Six Powerful Motivations Driving Social learning by Teens. Retrieved March 30, 2015, from MindShift: Http://blogs.kqed.org/mindshift/2015/03/six-powerful-motivations-driving-social-learning-by-teens

Rheingold, H. (2010, October 7). Attention, and Other 21st-Century Social Media Literacies. Retrieved March 21, 2015, from Educause: http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/attention-and-other-21st-century-social-media-literacies

Rheingold, H. (2012). Netsmart: How To Thrive Online. London: MIT Press.

Richardson, W. (2010). Navigating Social Networks as Learning Tools. In 21st Century Skills: Rethinking How Students Learn (pp. 285-304). Bloomington: Solution Tree.

Richardson, W., & Mancabelli, R. (2011). Personal Learning Networks: Using the Power of Connections to Transform Education. Bloomington: Solution Tree Press.

Simkin, M. (2015, April 28). Artefact Design. Retrieved from Digitalli: http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/msimkin/2015/04/28/artefact-design/

Simkin, M. (2015, April 27). Social Media in Your Classroom. Hamilton, Victoria, Australia. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YS39JMf6iwA

Simkin, M. (2015, April 29). Survey Results. Retrieved from Digitalli: http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/msimkin/2015/04/29/survey-results/

Statt, T. (2015, May 1). History teacher. (M. Simkin, Interviewer)

Weinberger, D. (2011). Too Big To Know: Rethinking Knowledge Now That The Facts Aren’t Facts, Experts Are Everywhere, And The Smartest Person In The Room Is The Room. New York: Basic Books.

Wenger, E. (2012). Communities of Practice a Brief Introduction. Retrieved from Wenger Traynor: http://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/

Wheeler, S. (2015, March 21). Making Connections. Retrieved March 23, 2015, from Learning with ‘e’s My Thoughts About Learning Technology and All Things Digital.: http://steve-wheeler.blogspot.com.au/2015/03/making-connections.html

Wong, S. L., Hanafi, A., & Sabudin, S. (2010). Exploring Teachers’ Perceptions of Their Pedagogical Role With Computers; a Case Study in Malaysia. Procedia: Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2, pp. 388-391.

Zuckerman, E. (2013). Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection. New York: W.W Norton & Company.